The potato is served with more false beliefs than butter. Its true character is so clouded that people automatically place it in the same put-on-pounds category as chocolate cake and banana splits, convinced that it in long on starch, fat and carbohydrates, short on protein and vitamins.

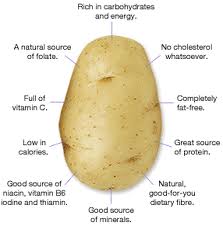

But the truth is we would have to eat 11 pounds of potatoes to put on one pound of weight. Ounce for ounce, a boiled, medium-size potato, at only 76 calories, has no more calories than the keep-the-doctor-away apple, and fewer than cottage chesses, avocados, rice or bran flakes. What’s more, though Americans, for instance, spend only two percent of their food dollar on potatoes, they receive from that small amount their most economical, nutritionally balanced, staple food. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that if a person’s entire diet consisted of potatoes, he would get of the riboflavin (B2) 1-1/2 times the iron, three to four times the thiamin (B1) and niacin (B3) and more than ten times the amount of vitamin C that the body needs.

But the truth is we would have to eat 11 pounds of potatoes to put on one pound of weight. Ounce for ounce, a boiled, medium-size potato, at only 76 calories, has no more calories than the keep-the-doctor-away apple, and fewer than cottage chesses, avocados, rice or bran flakes. What’s more, though Americans, for instance, spend only two percent of their food dollar on potatoes, they receive from that small amount their most economical, nutritionally balanced, staple food. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that if a person’s entire diet consisted of potatoes, he would get of the riboflavin (B2) 1-1/2 times the iron, three to four times the thiamin (B1) and niacin (B3) and more than ten times the amount of vitamin C that the body needs.

None of these facts were known to Peru’s Inca Indians, who first cultivated the potato in about 200 B.C. Millions throughout the world are indebted to that culture-and to the looting Spanish conquistadors who in 1537 first found the potato in the Andean village of Sorocota.

Ranging in size from a nut to an apple, in color from gold and red to gray, blue and black, the strange vegetable of the Incas had many uses. Raw slices were placed on broken bones, rubbed on the head to cure aching, carried to prevent rheumatism and eaten with other food to prevent indigestion. The Incas even knew how to preserve their staple food indefinitely. The potatoes were taken to 13,000 feet in the Andes, where they froze at night, then thawed in the sunlight. This process was repeated until the potatoes were without moisture, hard but very light- the world’s first freeze-dried food.

The Incas’ general name for this miracle plant of 52 varieties was papa, meaning tuber. The Spaniards preferred to call it turma de tierra, or truffle. They found it “floury, of good flavor, a dainty dish even for Spaniards.”

But when they introduced the potato to Europe some 400 years ago, it immediately became the victim of myths and slander. Since it is not mentioned in the Bible, it was thought to be unfit for human sue, And because it was not grown from seed, it was said to be evil, responsible for leprosy, syphilis and scrofula, French experts claimed it would destroy the soil in which it was planted, and physicians there said it was responsible for several serious illnesses and was a dangerous aphrodisiac.

It took at least two centuries after their export from South America for potatoes to be accepted and developed in Europe. England, for instance, did not produce them in any quantity until 1796 (though earlier, probably in 1663, that country did send some to Ireland where they were promptly planted and appreciated).

The United States got its first potatoes in 1719 when a colony of Irish settled at Londonderry, New Hampshire. But even there potatoes were slow to win favor. As late as 1740, masters advised apprentices that they were not obliged to use potatoes, which were said to shorten men’s lives. It was only after a few of the upper class pronounced them palatable that the ne vegetable became popular.

It even took nutritionists a long time to rally around the potato. However, within the last few years they have been preaching that potatoes not only are a good source of essential amino acids, but are also high in potassium-a valuable aid in treating digestive disorders.

In addition, the potato gives excellent nutritional return for every gram of carbohydrate it contains. It is such a near-perfect food that the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture has declared that “a diet of whole milk and potatoes would supply almost all of the food elements necessary for maintenance of the human body.”

In addition, the potato gives excellent nutritional return for every gram of carbohydrate it contains. It is such a near-perfect food that the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture has declared that “a diet of whole milk and potatoes would supply almost all of the food elements necessary for maintenance of the human body.”

Noted nutritionist Jean Mayer says that people are obsessed with the idea that starchy foods are “horribly” Fattening. Yet the fact is that the potato has fewer calories than believed and contains good-quality, easily digestible protein in ten percent of every 100 calories. Nutrition research studies indicate that when starch, as in potatoes, is substituted for sugar in the diet, appetite is lessened. Bulky, packed with vitamins and minerals, potatoes are valuable in a balanced reducing diet. Even ten 1/2×1/2×2-inch slices of fried potatoes amount of just 137 calories. Compare that with the 225 calories for a cup of cooked rice, and compute the relative food values. The potato comes out far ahead in its balance of nutrients.

Although it is hard to beat that easy standby, the baked potato drenched in butter, Americans keep trying. They blend the mealy baking potatoes with everything from cottage cheese to caviar and salmon. They also hash, mash, mince, cream, fry, steam, boil and roast potatoes; even make delicious chocolate cake with them. They also invented potato chips, and produce four billion pounds just to satisfy the average American’s appetite for 4-1/2 pounds per annum.

Still, their most popular potato dish was invented by the French. But the French, who fondly call the potato pomme de terre, “apple of the earth,” do much more than “French fry” them. They have over 100 classic recipes, from the dramatic pommes de terre soufflées which puff into hollow golden balls, to the impressive pommes Anna, sliced very thin, baked in sweet butter and turned out like a cake.

The Germans have two names for the potato: kartoffel, or truffle, and erdapfel, earth apple. They use it for moodles, dumplings, pancakes and bread; imaginatively mix mashed potatoes with applesauce, sugar and vinegar; use potatoes to stuff geese; and make a renowned hot potato salad. The Italians turn the patate into their famous gnocchi. The Spanish fill a spectacular omelette with papas, the Greeks make a superb sauce, skordalia, with potato, olive oil, garlic and lemon.

The world’s ways with the potato are endless, but its first producers, the Peruvians, may have the most imaginative touch. They have created the lusty, justly famous causa a la limena – mashed potatoes mixed with lemon juice, olive oil, chopped onions, salt, pepper and spine-stiffening hot chili peppers.

The world’s ways with the potato are endless, but its first producers, the Peruvians, may have the most imaginative touch. They have created the lusty, justly famous causa a la limena – mashed potatoes mixed with lemon juice, olive oil, chopped onions, salt, pepper and spine-stiffening hot chili peppers.

The poor man’s food and the gourmet’s delight also has, historically, come full circle in the country of its origin. In La Molina, Peru, at the International Potato Center, 86 scientists from 23 countries are creating “Super Spud.” Their objective: to perfect a potato that will grow fast in the humid tropics where millions of the hungriest poor live. The plan is for Super Spud not only to become an important food source in those areas where it is presently unknown, but to have its rapid growth prevent storage problems.

The cent’s scientists have advanced to the point of developing Super Spud into edible tubers in 31 days, maturity in 60 days (an Idaho or Maine potato takes 120 days). Right now they are working on the last obstacle: a completely disease-resistant for the poor farmers in the tropics who have no pesticides available, and couldn’t afford them if they did.

Thus, the humble vegetable from Peru may soon leave its homeland on its second and most important journey – to wipe out world hunger