On the night of July 20, 1973, just as suddenly as he shot into international fame, boxer-actor Bruce Lee collapse at a friend’s house. He was rushed to hospital, where he died soon afterward of acute cerebral oedema (brain swelling.) But the legend of Bruce Lee did not end with his death. Long after his films were first released, lines have been forming in front of theaters throughout Asia, the United States and Europe. In Japan, he was voted top male actor of 1974. Books have been written about him, and several films based on his life have been made.

On the night of July 20, 1973, just as suddenly as he shot into international fame, boxer-actor Bruce Lee collapse at a friend’s house. He was rushed to hospital, where he died soon afterward of acute cerebral oedema (brain swelling.) But the legend of Bruce Lee did not end with his death. Long after his films were first released, lines have been forming in front of theaters throughout Asia, the United States and Europe. In Japan, he was voted top male actor of 1974. Books have been written about him, and several films based on his life have been made.

Virtually unknown two years before his death, Bruce Lee took Southeast Asia by storm. His first film, “The Big Boss,” broke box-office records in Hong Kong and Singapore. In Hong Kong, it grossed nearly HK$3.2 million, shattering by HK$700,000 the previous box-office record, held by “The Sound of Music.” In Singapore, it grossed some S$2 million in four weeks, also an all-time record.

The success of Bruce Lee’s third film, “The Way of the Dragon,” which he directed himself, boggles the imagination. In its first run in Hong Kong, it grossed a staggering HK$5.3 million. Never before had an actor caught the public’s imagination so fast, nor held it more compellingly. “The Way of the Dragon,” Bruce’s last completed film.

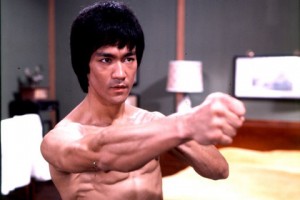

Whenever his films are shown, the atmosphere inside the theaters is electric. Audiences explode in whoops and applause each time the handsome boxer lets loose with his flying triple-kick, his straight jabs and short hooks. He whirls a linked-club with dazzling speed, and those who get in its way fall like so many flies; he breaks four dangling one-inch-thick wooden boards with a side kick, and when he glowers toward the cameras, audiences seem to recoil as though he were about to leap at them from the screen.

“There have been many martial-art heroes of the screen, but the audience is never sure whether they do their own fighting,” says Raymond Chow, president of the Golden Harvest Film Co., which produced Bruce Lee’s films. “Bruce was real fighter, and the audience knows the difference.”

More than that, Bruce had kicked martial-art tradition into smithereens and opened the door to a new concept of boxing which he called “Jeet Kune Do.” Explained Bruce, “What I’m pursuing is absolute freedom and ultimate liberation. In martial art there should be no such thing as style or school. If you unthinkingly follow this style or that school, you’re limiting yourself, turning yourself into a machine. Fighting, like life, is a never-ending learning process.”

The current result of that learning process was a fighter who studied philosophy, a teacher turned film-maker, a five-foot-eight, 140-pound human dynamo looking for new fields to conquer.

Son of the well-known Cantonese opera singer Lee Hai-chuen, Bruce Lee was born in San Francisco in 1940 when his parents were on a performing tour of the United States. They returned to Hong Kong when Bruce three months old. Home was happy and noisy. “We had to be careful with money,” Bruce recalled, “not because Father didn’t make enough but because more than 20 relatives depended on him for support.”

Since the boy showed an early interest in show business, Lee Hai-chuen arranged for him to appear during summer vacations. His performances so impressed veteran director Chin Chien that he cast the boy as the star of a film called “The Orphan in the Sea of Bitterness” in the late 1940s.

After that, Bruce might have become merely one of hundreds of other good actors, had it not been for an incident which happened when he was 13. He and a schoolmate were walking down a street, when they were threatened by three teen-age toughs. Bruce wanted to run, but his friend, a student of the Yung Chun Pugilism School, drove the three bullies off with a series of deft and powerful punches and kicks. The very next day, Bruce enrolled at the school to study with its top pugilist Yeh Wen.

After that, Bruce might have become merely one of hundreds of other good actors, had it not been for an incident which happened when he was 13. He and a schoolmate were walking down a street, when they were threatened by three teen-age toughs. Bruce wanted to run, but his friend, a student of the Yung Chun Pugilism School, drove the three bullies off with a series of deft and powerful punches and kicks. The very next day, Bruce enrolled at the school to study with its top pugilist Yeh Wen.

Lee Hiai-chuen objected to the boxing lessons because he wanted Bruce to devote more time to his school books, but Bruce was no ordinary schoolboy, and showed an early aversion to being confined to the classroom. “It never hurts to learn one more skill,” he argued. Bruce trained under this great master for six years, becoming his star pupil.

In 1958, upon the urging of his father, Bruce crossed the ocean again and enrolled at the University of Washington to major in philosophy. Fans unaware of Bruce’s many-sided personality might find this surprising but Bruce himself explained, “The thing about life is, you have to learn in order to be prepared. Then when the unexpected challenge arises, you are able to meet to.”

Respectfully declining his father’s financial support, he paid his college expenses primarily by teaching the art of self-defense at the UMCA. Although an “A” student, he chose to leave school after finishing his junior year: he left ready to meet the unexpected challenge. A year before, he had rented a basement in Seattle, on the West Coast of America, for $20 a month and set up his own martial-art school, charging $15 a month for each student. He had 15 that year. By the time he returned to Hong Kong to take part in “The Big Boss,” he was operating karate schools in Los Angeles, Oakland and Seattle. His instruction fees rose to $275 for one lesson or $1000 for ten sessions and his students included not only Chuck Norris, Joe Lewis, Mike Stone and Louis Delgado, all of whom became karate champions, but also American movie actors Steve McQueen, James Coburn and Dean Martin.

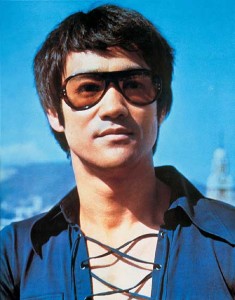

In 1964, he fell in love with one of his students, Linda Emery, then a pre-medical student at the University of Washington. Six months later, they were married. The first year of marriage was also the initial year of Bruce’s rise to stardom. As United States, he was invited to give a demonstration at the 1964 International Karate Championships, in Long Beach, California. He stepped onto the stage, wisecracked, punched and kicked. In the audience was a producer of 20th Century Fox who immediately phoned Bruce and signed him up to play the role of Kato in “The Green Hornet” TV series. The series was show in Southeast Asia as well as the States. But, since Kato seldom took off his mask, few people became familiar with his face. Before achieving stardom he would need additional public exposure.

However, even before attempting to overcome the lack of public exposure, Bruce Lee decided he had to “overcome” himself. For long he had sought ways of innovating on the martial art, of offering suitable modern additions to its classical heritage. “But the more I trained and practiced, the more I felt that there was a barrier I couldn’t break through,” he complained.

From this agonizing eventually was born the concept of Jeet Kune Do. “Everybody is built differently,” Bruce explained. “The key to winning is finding the weak spots in yourself – by finding out what is not, you are closer to what is. You cannot do that if you confine you-self entirely to tradition.

From this agonizing eventually was born the concept of Jeet Kune Do. “Everybody is built differently,” Bruce explained. “The key to winning is finding the weak spots in yourself – by finding out what is not, you are closer to what is. You cannot do that if you confine you-self entirely to tradition.

For the next several years he worked to develop new movies which connoisseurs would accept as a modern enhacement of the martial art in harmony with its ancient tradition.

In 1970, Bruce decided to return to Hong Kong. He wanted to blend his acting experience with his innovations in the martial art. When Raymond Chow, who had been impressed with Bruce’s TV performances, heard of his plans, he signed him to star in “The Big Boss,” which was filmed in Thailand and released in November 1971.

After the success of his movies, Bruce closed his karate schools, but, to keep in shape, he ran six miles daily and worked out punching and kicking for an hour. When he was filming, he cut the running to a mile-and-a-half.

The almost fanatical application Bruce once reserved for the martial art was now turned with equal force on the art acting. During shooting breaks he rehearsed the upcoming scene again and again, until he was satisfied. “He was constantly thinking of ways of improving the film,” said actress Yi Yi, who played with him in “The Big Boss.” While on location in Pak-Chong, Thailand, making the film, he once kept fellow actors awake until 2 a.m. considering ways of improving the work scheduled for the next day. To Bruce Lee the quest for perfection was never-ending.

Shortly before his death, he formed a film company in partnership with Raymond Chow. “I hope to make multi-level films – the kind of movie that has a deeper meaning beneath the surface story,” he said. “Most Chinese films have been superficial and one-dimensional.” Unfortunately, he never had the chance to fully realize this ambition.

“You learn from the martial art that you must never stand still,” Bruce said. “Stop moving, and you’re dead. That goes for the mind too, whether it applies itself to the making of films, or anything else!”

In this context, Bruce Lee still lives, for in the hearts of his fans, he is still on the move.